By Jeffrey Herf | Commentary, The Free Press

The global intifada comes to Boulder, Colorado, 11 days after the murders in Washington, D.C.

On Sunday afternoon in Boulder, Colorado, a group of Jews was set on fire. They had gathered in the afternoon for a march to draw attention to Israel’s hostages, who have been held by Hamas terrorists for more than 600 days, when a man reportedly threw a Molotov cocktail at the group, seriously injuring several.

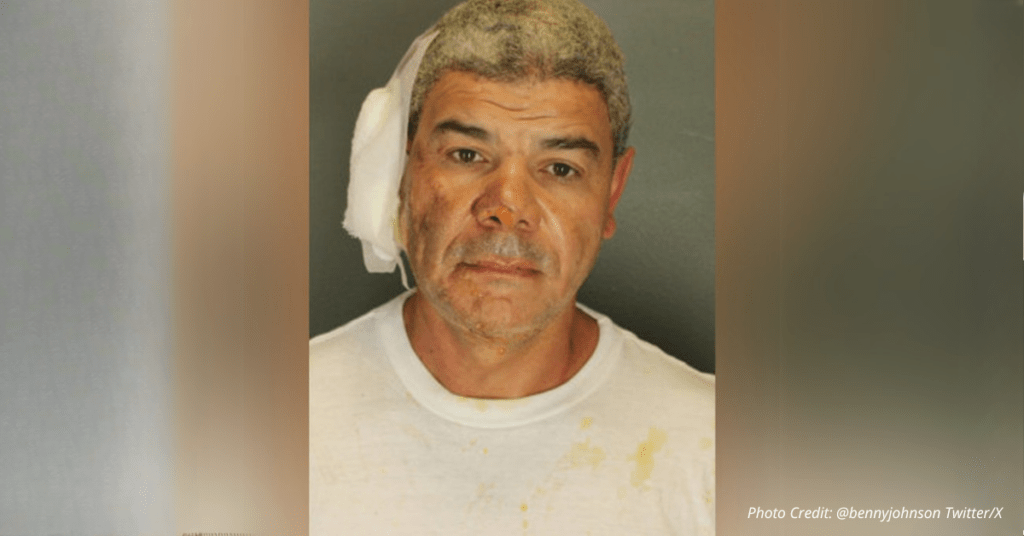

The alleged perpetrator is named Mohamad Soliman, and you can see him in videos from the scene shouting “End Zionists” and “Palestine free and for us.”

This incident, which the FBI has called a “targeted terror attack,” comes less than two weeks after the assassination of Yaron Lischinsky and Sarah Milgrim outside the Capital Jewish Museum. Their alleged killer, Elias Rodriguez, yelled exactly what the perpetrator in Boulder yelled—“Free Palestine”—the slogan that echoed on campuses and in the streets, especially since the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023.

These two events are of great historical significance.

They are terrorist attacks carried out against Jews in America in the name of “liberation” thousands of miles away. They were carried out by people who feel so emboldened by the global ideological assault on Israel and its supporters that they were willing to make the leap from hatred to violence. And if history is a guide, they will not be the last to do so.

In his 2003 book Terror and Liberalism, Paul Berman wrote that in the wake of suicide bombings against Israeli civilians in 2000 by Hamas and Islamic Jihad, “the popularity of the Palestinian cause did not collapse. It increased.” He adds: “There was, in short, an idea that each new act of murder and suicide testified to how oppressive were the Israelis. Palestinian terror, in this view, was the measure of Israeli guilt.”

It is likely, indeed probable, that these two attacks excite and stimulate others to further acts of violence. After all, the response on many campuses to the Hamas massacres of October 7 ranged from enthusiasm to apologia. Calls to end Israel’s existence “from the river to the sea” increased, and “pro-Palestinian” demonstrations and antagonism toward “Zionists” exploded at universities and colleges all over the United States.

These attacks—and the normalization of terror in our culture—recall a previous American leftist turn to terror, that of the Weather Underground, an offshoot of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). In the famous “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows” statement of June 18, 1969, its authors, including graduates of the University of Chicago, Columbia, the University of Michigan, and other well-known American universities, called for the creation of “Marxist-Leninist-Maoist collective formations” that would prepare for “revolutionary war.”

The story of the organization’s descent into bombings in the following years is well known.

To its followers, the appeal of the Weathermen’s ideology, captured in its statement, was its consequential radicalism. That is, its willingness to unite theory and practice, ideology and politics. If the American political and economic system was so utterly evil, then only “revolutionary war”—not peaceful reform—was essential to end injustice and create a new and good world. The step from reform and protest to revolution had the virtue of seeming to be the perfectly logical—indeed, unavoidable—implication of the ideological arguments that some parts of the New Left were making by the late 1960s. The leaders of the Weathermen accused those who shared the radical critique but refused to pick up arms of a mixture of cowardice and refusal to think through the implications of their own ideas.

The Weathermen attracted only several hundred followers, but the group inspired many others to engage in violence.

Back then most of the members of the American New Left—and even more so participants in the broader opposition to the American war in Vietnam—did not share in its logical leap from verbal radicalism to support for political violence. They rejected it. Emotionally, the criticism emerged from the hippie counterculture of rock music and “peace and love.” Intellectually, it came from small, left-leaning journals such as Telos and writers who rejected Marxism-Leninism as a regression behind the originality of the democratic promise of the New Left and the civil rights movement. Beyond a small leftist bubble, the Weathermen faced a climate of criticism and antagonism in the universities and the press.

Another key difference between then and now is that the professors in the humanities and social sciences were predominantly liberal, not leftist. Most professors of the 1960s neither promulgated nor endorsed the varieties of Marxism and Marxism-Leninism that came to dominate the Students for a Democratic Society by spring 1969.

To be sure, students who came of age in the 1960s who followed academic careers in the humanities and social sciences pushed the professoriat to the left. They adopted varieties of leftist criticisms of American capitalism, but they put their energies into teaching, research, and gaining tenure, especially in the humanities and social sciences. The romance with terror did not fit well with seeking tenure in major universities and colleges. In the United States, in contrast to the aftermath of the New Left in “post-fascist” West Germany, Italy, and Japan, during which leftist terrorist organizations engaged in political murders even into the 1980s, the Weathermen had faded from political significance by the early 1970s.

But what didn’t fade was the strain of radicalism on the left that demonized Zionists and Israel. By 1969, in the wake of Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War of 1967, both the Black Panther Party and SDS had turned decisively against Israel and celebrated terror, which they recast as “the armed struggle” of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Those ideas entered the subdiscipline of Middle East Studies and recast the history of Israel as one of racism and colonialism, and as part of the global system of imperialism that the New Left of the 1960s had denounced. By the 1990s, an anti-Zionist faculty had gained tenure at major universities, most importantly in history, English, and area studies departments. These professors supported Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) initiatives, and echoed Hamas propaganda during the wars Hamas launched after seizing power in Gaza in 2007. Their canonical works, such as Edward Said’s 1978 work Orientalism, brought the PLO’s version of Israeli history as one of colonialism and racism into the American academy and onto many course syllabi.

It was during these years that anti-Zionist passion and the delegitimation of Israel acquired academic respectability in American universities.

In parallel, an activist dimension emerged with the formation of Students for Justice in Palestine organization in Berkeley in 1993. This group established itself as a national organization in 2010, and by 2024 it claimed to have 275 chapters at universities and colleges. These chapters supported the BDS efforts and some advocated “armed struggle as the only way to liberate Palestine.” After October 7, others endorsed the Hamas attacks, and many called for “dismantling” Zionism on American campuses.

During the 2023–2024 academic year, academics at 120 universities and colleges formed Faculty for Justice in Palestine (FJP), which coordinates with SJP. FJP asserts that Israel has conducted a “violent, repressive occupation” of Palestinian territory and that this occupation is related to “interlocking systems of oppression underpinned by global white supremacy and racial capitalism.” FJP’s website refrains from criticism of Hamas and the Islamist religious war it has waged against Israel. Instead, it speaks in the secular language of the Western left when it states that it is “firmly committed to combating any form of racism, including anti-Arab and anti-Palestinian racism, Islamophobia, antisemitism, anti-Blackness, and white supremacy.” FJP does not advocate political violence, but it lends the prestige of the faculty, such as it is, to efforts to attack Israel’s moral and political legitimacy, and offer a distorted version of its history.

Elias Rodriguez and others who came of political age in the resulting ideological climate came to view the state of Israel as uniquely evil. The “question of Palestine” came to assume a central aspect to leftist politics and ideas. Support for the state of Israel became incompatible with other leftist causes. With the formation of Faculty for Justice in Palestine, that antagonism became not only a ubiquitous form of leftist student activism but has also attained academic respectability in the universities. As Cary Nelson has pointed out, as a recent graduate of the University of Illinois at Chicago, Rodriguez would likely have been exposed both to a curriculum and to activism saturated with such views.

READ THE FULL COMMENTARY AT THE FREE PRESS

Editor’s note: Opinions expressed in commentary pieces are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the management of the Rocky Mountain Voice, but even so we support the constitutional right of the author to express those opinions.